Below is an extract from ‘My Kind of Life’ an autobiography by Iris Martin, who has very kindly given us permission to publish on this site.

Iris would appreciate feedback, please email mark.mdavis@gmail with your comments.

Mark.

……………………….

MEANWOOD PARK HOSPITAL

My Grandma took me to the Salvation Army and I carried on going because it got me out of the house. I went to the branches in Brighouse and Halifax. I met my best friend, Mrs Barwick at the Sally Army in Brighouse. I used to go on a Monday to the Home League. It was all women together with two Officers, a man and a woman. I made tea, coffee and toast, gave the biscuits out and did the washing up. I helped at both places. On Wednesday’s I went to Brighouse. I was glad to get out of home. After I lost my job at the mint factory, Mrs Barwick got me into Meanwood Park Hospital in Leeds. I was about 17 or 18 years old when I went there [1957 or 1958].

It was a shocking place. You were locked in all the time. As soon as you went out, they locked the door. One day a new patient came and she used my soap. I told her she had to buy her own. She told another patient called Nora Russell. My hair was very long in those days, right down to my waist. Nora got hold of my hair and dragged me down these stone steps and I broke my wrist. Another time, a different patient knocked me out and my hand went through a window. The night nurse came and then the Sister came. The Sister didn’t say anything but she punched me and knocked me out again. I had to have stitches and I’ve still got the scar. When my wrist was in a pot, I couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t go to work. I worked in the sock factory there. We had to darn men’s socks. Across the road, there was the laundry, where they washed them. We darned socks all day long. Sometimes I helped with the garden, just digging the soil over. They paid us wages for working. Every week we could choose either 6d some chocolate. I usually chose the 6d because you had to buy things like soap and flannels and toothpaste. The hospital had its own shop.

At weekends, we put on our own clothes and we went out to the pictures or dancing. Not out of the gates but to another part of the hospital. I think somebody came in specially to show the films or to put the records on for the dances. They locked the big gates after them. I wasn’t bothered about the films but I liked the dancing. The rest of the time we had to wear their clothes. They were awful, all alike. It was like a gym slip but we were grown up. I was always glad to get them off.

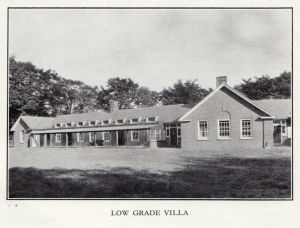

They were all snobs. I felt they all looked down on me even though I used to help there. I would help a nurse comb the hair of the low grades with water and Dettol to stop the nits. I was a high grade. I had two friends who were low grades. The man was called Lenny and I forget the girl’s name. They were both blind and they used to lead each other around. I would go and sit in the day room with them. We’d have the wireless on and we’d talk. Nora Russell would pull the plug out so we couldn’t hear the music. They got bullied too. Some of the nurses would tell them to go to the toilet by themselves or to other places even though they knew they couldn’t go by themselves. In another villa, there were children and even babies. It wasn’t right.

We all slept in a big dormitory. Nora Russell slept in a bed next to the door and she could see right across to me. She’d know if I got out of bed. Do you know what time we went to bed? Seven o’clock, even in the summer or at the weekends, except if there was a film or a dance when you could stay up until 10 o’clock. A nurse would stand by the window at the top and watch everybody. Why, I don’t know. If you wanted a cup of tea in the morning, Nora Russell said you had to make your bed first. If you didn’t, then she wouldn’t let you have any tea. You weren’t allowed to get your own and Nora wouldn’t help anyone. She’d say, ‘I’m in charge of this kitchen.’ Every morning, she put the kettle on and made the tea in a right big tea pot. We all had to get up at 7 o’clock. Everyone at the same time. The nurse would say, ‘If you don’t get up, I’m going to tip you out of bed.’ I thought to myself, ‘Oh no! Not me!’ They didn’t care if you were poorly, the doctors just made you to get out of bed. They pulled you out of bed even if you were asleep. The doctors and nurses would laugh at us. I didn’t like that.

I didn’t like their food. When it was fin haddock, I used to give mine away to the low grades, ‘Here have mine.’ We always had porridge for breakfast. They make it at Ferncliffe, where I live now, but it’s a lot better. They put honey on it now, not sugar, because I’m on a slimming diet. At Meanwood Park, I’d have three bites and that was it. It was thick and they didn’t put anything on it. The doctors used to spy on you in the morning, when you were having your breakfast. I didn’t like that. Even now, I can’t eat when I’m being watched. We’d come back from the sock factory for lunch. This was thick lumps of mashed potato with some sort of meat, I don’t know what it was but it was thick and lumpy, and vegetables. We sometimes had baked beans for tea.

You couldn’t go out of the gates and walk around like other people. They wouldn’t let you and I know why. Some people in our villa used to run away to the woods and there was a main road at the bottom. If you ran away, and they caught you, they locked you up in a side bedroom. They kept you there for 3 to 4 weeks. When the runaways came back to the ward, they told us that they only got bread and water. It was just like jail. They said they were caned as well. I wouldn’t run away. It wasn’t wise. I didn’t want to be caned, I’d been beaten enough. Anyway, I couldn’t run because my legs used to let me down a lot. I bet the little babies got smacked as well.

Once a month, they let us have visitors. The staff said if they came any other them, they wouldn’t let them in. They were only allowed to come into the dining room. Everyone sat around four big tables. Mum and Dad used to come and visit me and when it was time to go, they’d say, ‘Come to the gate by the toilets and tell us what is happening.’ And I’d say, ‘I can’t because the nurses will follow and listen to what I say.’ You couldn’t have a private conversation. The nurses would come and stand behind the settee and listen to what we were saying.

When the visitors had gone, the nurses took everything off you, everything your parents had brought for you, all the apples, oranges and drinks. They took it all away. Sometimes, I got a bit of it back but usually I never saw it again. Maybe they gave it to the low grades or maybe they kept it for themselves. Some people had no visitors. I thought it was very sad for them.

The only time I ever went out of the big gates was when I went home for holidays at Easter, Whitsuntide and Christmas. That’s when I told my parents what it was like at Meanwood. One day, my eldest brother Raymond had an argument with one of the doctors about them taking all my fruit. His name was Doctor Waters and he used to squint at you. Dr Waters turned his back on Raymond and walked out of the room. Nothing changed but soon after that they let me go home for good. I was at Meanwood Park for ten years. I was about 28 when I came out.

I moved back with Mum and Dad to Smith House Moor. I was very happy to be out of Meanwood Park. I could go to bed when I wanted, get up when I wanted, get undressed when I wanted, eat proper food that I liked and I could go out again. I didn’t want to stop at home all the time so I went back to the Salvation Army.

Sometimes, I feel very upset when I think what other people have done to me. If I could, I’d like to change my life completely. I’d get rid of my fits, the aches and pains and being knocked down for money.

I’ve never asked anyone for money, I’d rather do without. I’d get rid of Meanwood Park as well. Anyway, it’s gone now, they’ve pulled it down. That’s one good thing, they can never send me back there.

Now, I’m 68 and there’s nothing really I look forward to. I think I’ve had it. I’ve had my life.